The man with the instruments in space

Nicolas Thomas wants to understand Mars, comets and the icy moons of Jupiter. To do so, he builds instruments that fly through space on of board space probes.

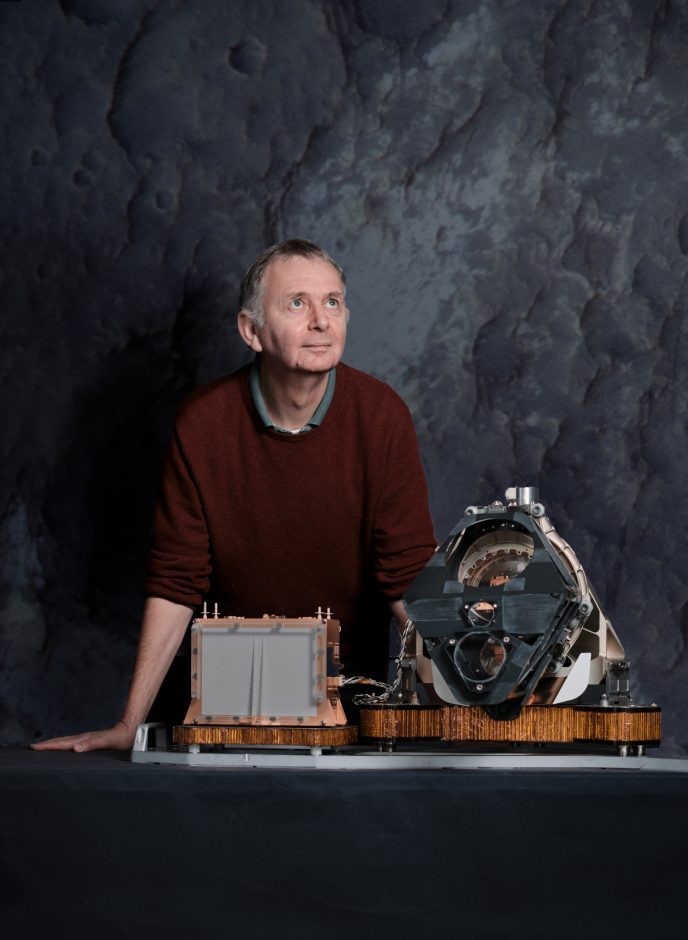

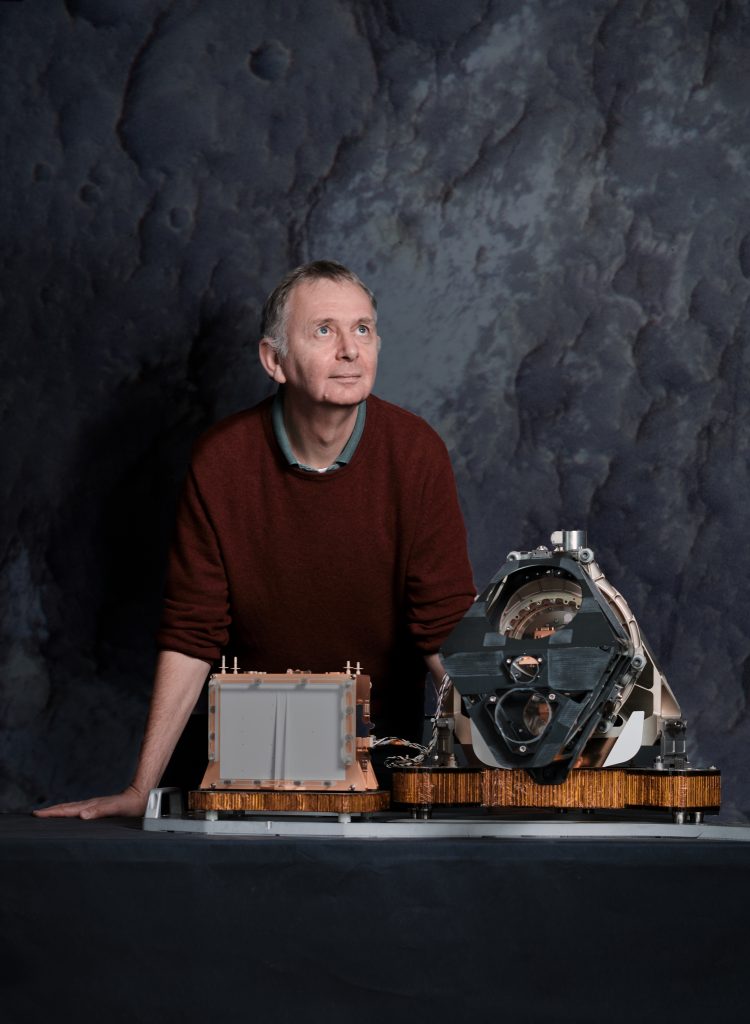

Nicolas Thomas joined the University of Bern in 2003. He has been Director of the Institute of Physics since 2015 and also of the National Centre of Competence in Research PlanetS since June 2022. Image: University of Bern

By Brigit Bucher

When asked how he came up with the idea of becoming an astrophysicist, the answer comes lightning-fast: “Quite clearly: because of the first moon landing. When Armstrong walked on the moon, I was eight years old and an absolute technology freak. I just knew everything about the US space programme.” So it was all the more disappointing that his mother sent him to bed and Nicolas Thomas was not allowed to watch the first moon landing live on TV.

Nicolas Thomas grew up in Shrewsbury; he regularly returns to England to visit his two aunts who are over 80 years old. He completed his doctorate at the University of York in 1986 and then worked at the Max Planck Institute, with stays at ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk as well as the University of Arizona in the USA. In 2003, he came to the University of Bern and has been Director of the Institute of Physics since 2015.

The Magic Triangle of Bern

“There was this colleague who really wanted to get me to France in 2003. He said: Why do you want to go to a village like Bern? And I replied: the University of Bern is one of the best places in the world to do space research.” Not only in terms of building space instruments for large space organisations such as ESA, NASA or JAXA, Bernese space research is at the top of the world, Thomas says, but also in experiments in the laboratory as well as in creating models and simulations of the formation and development of celestial bodies. “It’s like a magic triangle that exists in space research only in a few places in the world,” Thomas points out. Then there is the more than 50-year tradition and the networks that have been continuously expanded since the University of Bern’s participation in the first moon landing with the solar wind sail experiment.

Buzz Aldrin unfurls the solar wind sail, developed at the University of Bern, on the moon on 21 July 1969. © NASA, Apollo Image Archive

We talk about science today. “Many people expect immediate answers from science and don’t understand that building knowledge sometimes takes a long time. Planetary research, for example, is more of a marathon than a sprint. It is rather rare that there is a breakthrough from one day to the next, and these are usually connected with space missions.

When asked about his personal major successes in his career, Nicolas Thomas says: “The successes I’m probably most proud of are those where we’ve gone a long way towards solving a particular problem.” One such project was related to data returned by the Rosetta space probe from comet Chury. “The question we were trying to answer was why there is so much dust over the night side of the comet’s nucleus. Our results won’t bring the president to come by to congratulate us. But I’m very pleased that, based on our data analysis and modelling work, we’ve been able to answer this question that had been unanswered for 35 years.” (Spoiler alert: The night page is active.)

Thomas is also proud of the CaSSIS camera, which was built under his direction and has been providing high-resolution, colour images of the surface of Mars on board the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter spacecraft since 2016. “This spring, a large illustrated book was published with the 200 most beautiful CaSSIS images. These are really fantastic images,” he says, “but real top-level science takes place with other instruments.” For example, with the BELA laser altimeter on board the BepiColombo space probe, which is on its way to Mercury and will take measurements of the surface of the hottest planet in our solar system there from 2026: “Building BELA was undoubtedly the biggest challenge of my career. No one had ever built such an instrument before us. And it had to be designed in such a way that it would also function at the hellish temperatures at Mercury.”

BELA at the Physics Institute of the University of Bern. © University of Bern

Fascination Rocket Launch

I ask him how he feels every time his instruments are launched into space on board a rocket. He laughs: “I’ve been to many rocket launches, they are great fun! When a rocket takes off, it’s very impressive. But I only get nervous about 30 days after the launch, when the instrument is switched on for the first time. Then I always think: What will I tell the team, the people who financed the instrument, the press, if the thing doesn’t work? That scares me a little bit each time.” His biggest disappointment was when Beagle 2, the lander on board the Mars Express spacecraft with a microscope built by Nicolas Thomas, didn’t work: “On 25 December 2003, my student and I went to Milton Keynes over Christmas to start analysing the data. And it turned out that the lander had failed because I guess it hadn’t deployed properly.” What he also finds frustrating is that there is often no clearly defined funding plan for the scientific analysis of the data from a space instrument: “You win a competition to build an instrument for a space mission. And then there is no clearly defined funding apparatus for the use of the data. A solution should have to be found for that.”

The launch of BepiColombo on 20 October 2018. image: Nicolas Thomas

Thomas has specialised in three topics in his research: the icy moons of Jupiter, comets and Mars. He specifies: “Everything I do has to do with ice. I’m interested in the ice under the surface of Mars, comets, which are largely made up of water ice, and in the case of the Jovian moons the focus is also on the water ice on the moon Europa as well as the sulphur dioxide ice on the moon Io.” And so Thomas was recently selected to be part of a team for NASA and the Canadian Space Agency for a mission called Mars Ice Mapper, where the goal is to map ice on Mars. The question of life on Mars does not concern Nicolas Thomas much, he is more interested in the evolution of the red planet and the processes that had an impact on it. Mars is particularly hot at the moment, as Thomas explains: “Various space agencies are preparing for a manned Mars programme. They’re going to the moon first and then Mars.” When does he think the first human will set foot on Mars? “So far, it has always been said in 30 years. When that number gets smaller than 30, only then will I start to believe it.”

Committed and enterprising

Nicolas Thomas will retire in 2026. Until then, he still has many plans. From summer 2022, he takes over from Willy Benz as director of the National Centre of Competence in Research NCCR PlanetS, which the University of Bern is managing jointly with the University of Geneva. In addition, the “CoCa” camera system for the “Comet Interceptor Mission” is being built in Bern under his leadership. The goal is to “park” a space probe in space, which will then head for a comet or an interstellar object on demand and explore it. He is also tinkering with a completely new type of instrument. “The idea came up in a discussion with laser physicist Thomas Feurer at the end of a long day,” he says with a laugh, “when we still liked the idea the day after, we got to work.” Promoting young talent is still important to him. “It’s important to me to give young people the self-confidence it takes to find their own research direction and their own questions.” And he wants to enable them to critically question their approach and the assumptions they have made again and again.

Nicolas Thomas at a special event on Bernese space research at the University of Bern © University of Bern

And what does his family think of the busy astrophysicist’s work? Nicolas Thomas thinks for a while and then says: “I guess they’ve kind of got used to it. We rarely talk about my work, every few months I show them a picture of CaSSIS, and of course they always want to know everything when I go to a rocket launch.” Will his children also follow the path to science? His 14-year-old daughter is very interested in veterinary medicine at the moment. The 16-year-old son, he says, is very talented in video and has programmed some kind of Hawk-Eye software for Cricket. “When I’m building a space instrument, it can happen in the final phase that I work twelve or more hours a day for a long time, but they understand that.”

One thing that annoyed his daughter was that he had been writing a book about the current state of comet research for three years and was very absorbed at times. “But that didn’t stop her from doing the drawing for the cover,” he says, smiling and holding the book up to the camera.

A German version of this text first appeared in Uniaktuell magazine.

Categories: External Newsletter, user_portrait