Highlights of recent research results

Recently, PlanetS researchers published papers about stolen comets, a forbidden planet, meteorites from Vesta, and Rare-Earth metals in the atmosphere of a glowing-hot exoplanet.

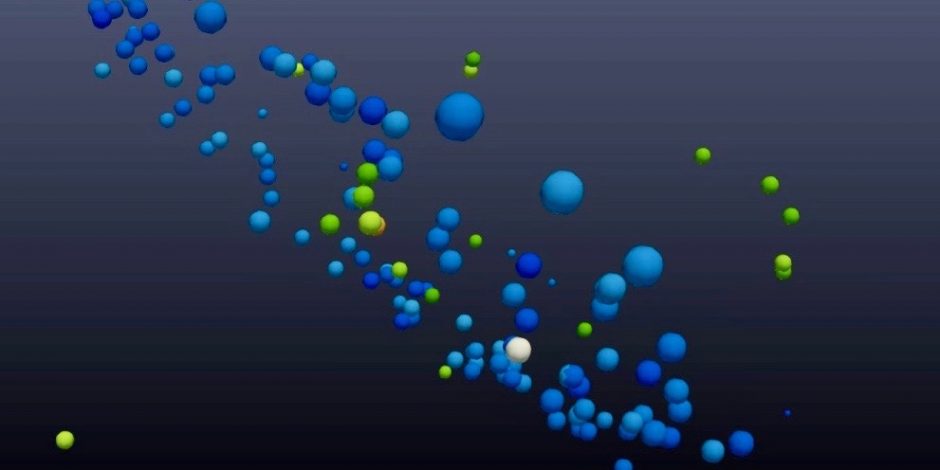

The video based on computer simulations demonstrates what happens if two young stars in a cluster undergo a close encounter. Each star has a belt of so-called planetesimals, the building blocks of planets, like the Kuiper belt in the outer Solar System. When the two stars meet, the Kuiper belt of the smaller star is heavily disrupted by its higher mass sibling. “This causes a bunch of planetesimals to be ejected, flying away to become things like Oumuamua,” explains Tom Hands, member of PlanetS at the University of Zürich. The strange cosmic object was the first known interstellar visitor of our Solar System.

The simulations show that a close encounter not only sends objects hurtling through inter-stellar space, but some of the bodies are forced onto bizarre orbits or even captured by the passing star. Our own Sun was most likely formed in a similar environment some 4.5 billion years ago, meaning it might have undergone similar encounters. “I was surprised by the ease with which stars can steal material from their stellar siblings at a young age,” says Tom Hands. So, our Solar System may contain alien comets that were stolen from another star in these early phases. More details: http://nccr-planets.ch/blog/2019/05/24/stolen-comets-and-free-floating-objects/

A forbidden planet

An international team of astronomers including members of PlanetS, have found a “forbidden” planet in an area known as the Neptunian Desert, a place where it should not exist. Also known as NGTS-4b, the exoplanet has a mass of 20 Earth’s and a radius that is 20 percent smaller than Neptune. Orbiting its star every 1.3 days, it has a temperature approaching 1,000 degrees Celsius. Yet, it still has its own atmosphere, something that has caused researchers to scratch their heads.

“This planet is right in the zone where Neptune-sized planets could not survive”, says François Bouchy, professor at Geneva University and member of PlanetS. “It is truly remarkable that we found a transiting planet via a star dimming by less than 0.2 %.”NGTS-4 was observed using a single NGTS camera over 272 nights from the Next Generation Transit Survey in northern Chile. It’s unclear why the planet is able to exist in the Neptunian Desert, though the researchers have offered two explanations: it moved into the region within the past 1 million years or it was very big and the atmosphere is still evaporating. More details: http://nccr-planets.ch/blog/2019/06/03/forbidden-planet-found-in-neptunian-desert/

Ambassadors from Vesta

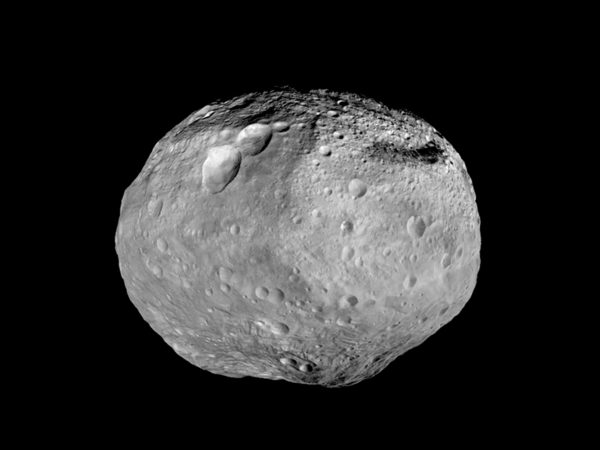

View of the asteroid Vesta provided by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft. Dawn studied Vesta from July 2011 to September 2012. (Image NASA)

Researchers from the group led by Maria Schönbächler, professor at the Institute for Geochemistry and Petrology at ETH Zurich and member of PlanetS, have determined the age and origin of five meteorites of a class known as mesosiderites. These are made up of silicate rock fragments and metal (typically iron and a small amount of nickel). As the two components have a disordered structure, scientists assume that they must have come from a “differentiated asteroid” – that is, from a celestial body that once had a crust, a mantle and a liquid core.

The researchers found that the rocks are over 4.5 billion years old and originate from Vesta, the second-largest asteroid in the main belt. “As a rule, it’s very difficult or even impossible to assign meteorites to specific original asteroids,” explains Maria Schönbächler. The researchers settled on Vesta not only based on the dating and chemical composition of the analysed mesosiderites, but also thanks to observational data from the NASA mission “Dawn” that pointed to this asteroid as the source. More details: https://www.ethz.ch/en/news-and-events/eth-news/news/2019/06/stony-ambassadors-from-the-asteroid-vesta.html

Rare-Earth metals in the atmosphere of a hot gas giant

KELT-9 b is the hottest exoplanet known to date. In the summer of 2018, a joint team of astronomers from the universities of Bern and Geneva and members of PlanetS found signatures of gaseous iron and titanium in its atmosphere. Now these researchers have also been able to detect traces of vaporized sodium, magnesium, chromium, and the rare-Earth metals scandium and yttrium. The latter three of these have never been detected robustly in the atmosphere of an exoplanet before. The team observed the hot gas giant with the HARPS-North spectrograph on the Italian National Telescope on the island of La Palma.

The atoms that make up the gas of the planetary atmosphere absorb light at very specific colors in the spectrum, and each atom has a unique “fingerprint” of colors that it absorbs. These fingerprints allow astronomers to discern the chemical composition of the atmospheres of planets that are many light-years away.“The chances are good that one day we will find so-called biosignatures, i.e. signs of life, on an exoplanet, using the same techniques that we are applying today. Ultimately, we want to use our research to fathom the origin and development of the solar system as well as the origin of life,” says Kevin Heng, Director and Professor at the Center for Space and Habitability (CSH) at the University of Bern and a member of PlanetS. More details: http://nccr-planets.ch/blog/2019/05/09/rare-earth-metals-in-the-atmosphere-of-a-glowing-hot-exoplanet/

Categories: External Newsletter, Uncategorized