Cassini – the big dive

On September 15, 2017, the Cassini probe completed its last orbit around Saturn before diving into its atmosphere. A touching end to the mission for the team of planetary scientists, engineers and other researchers who have been following the spacecraft’s feats since its launch 20 years ago.

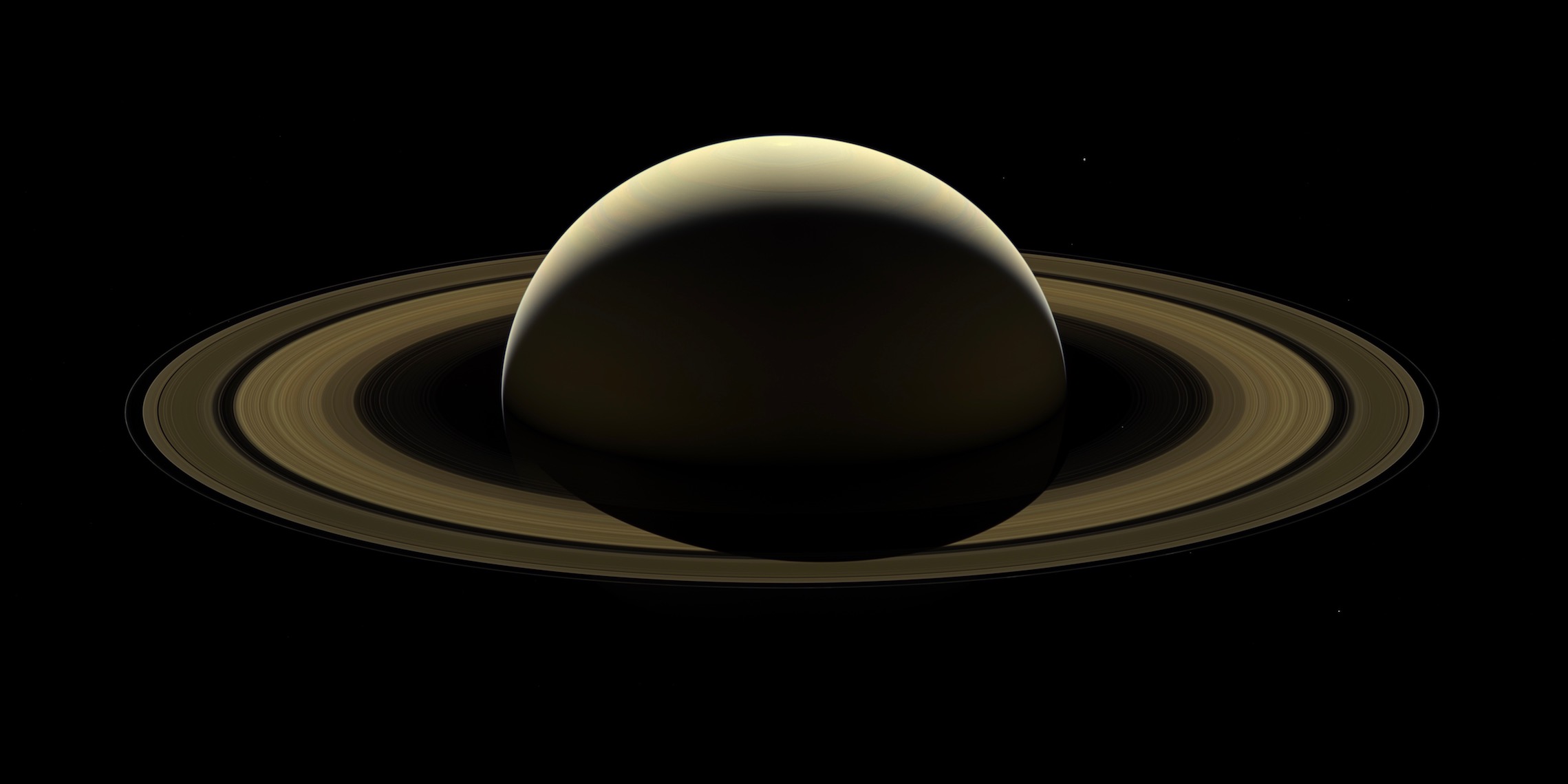

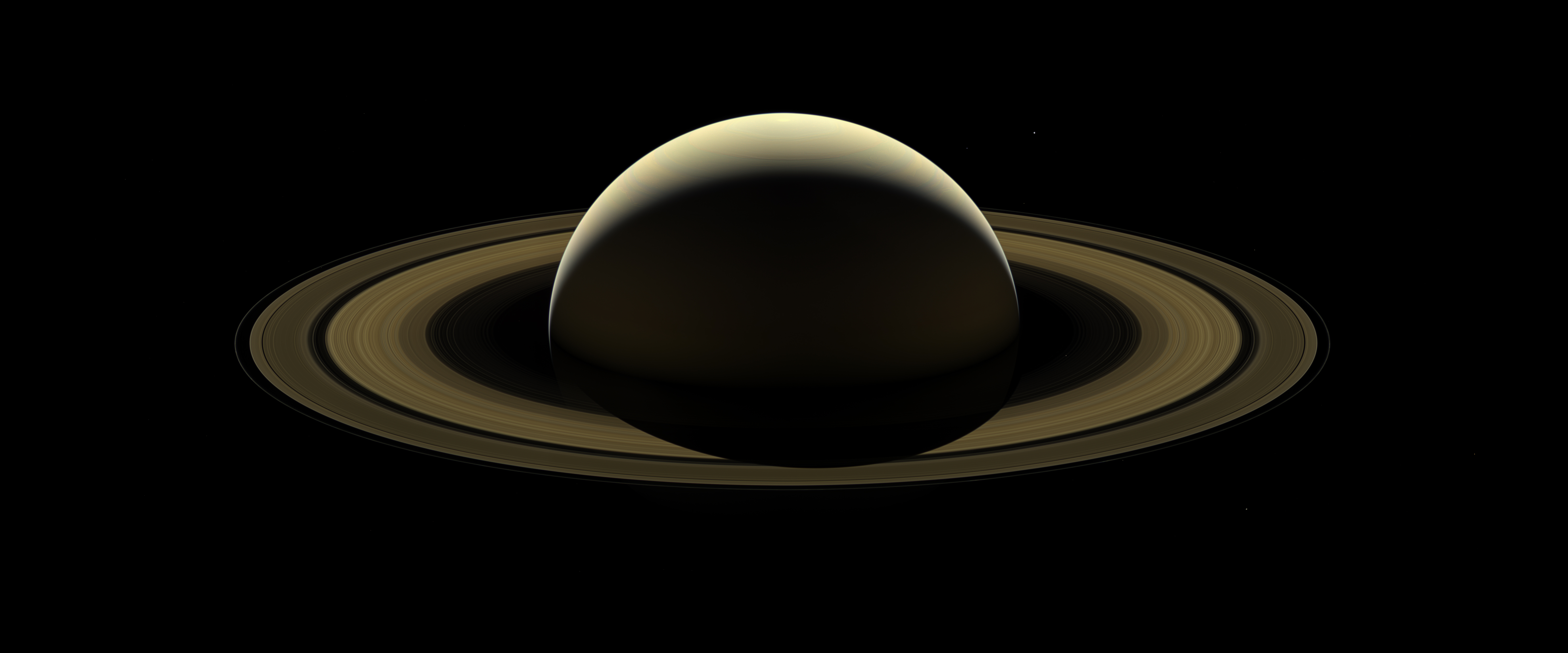

One of Cassini’s last looks at Saturn. (Image NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

“If we let the spacecraft indefinitely orbit Saturn, one day it could hit one of its potentially habitable satellites,” explains Ravit Helled, University of Zurich professor and PlanetS member, ” precipitating Cassini on Saturn we avoid a possible bacteriological pollution of the system of Saturn”.

If the ecological concerns of scientists are real, they are certainly not the ones that interest them the most. This last part of the Cassini mission, called “Grand Finale”, may make possible to precisely measure the gravity field of the planet, and from there to deduce its internal structure.

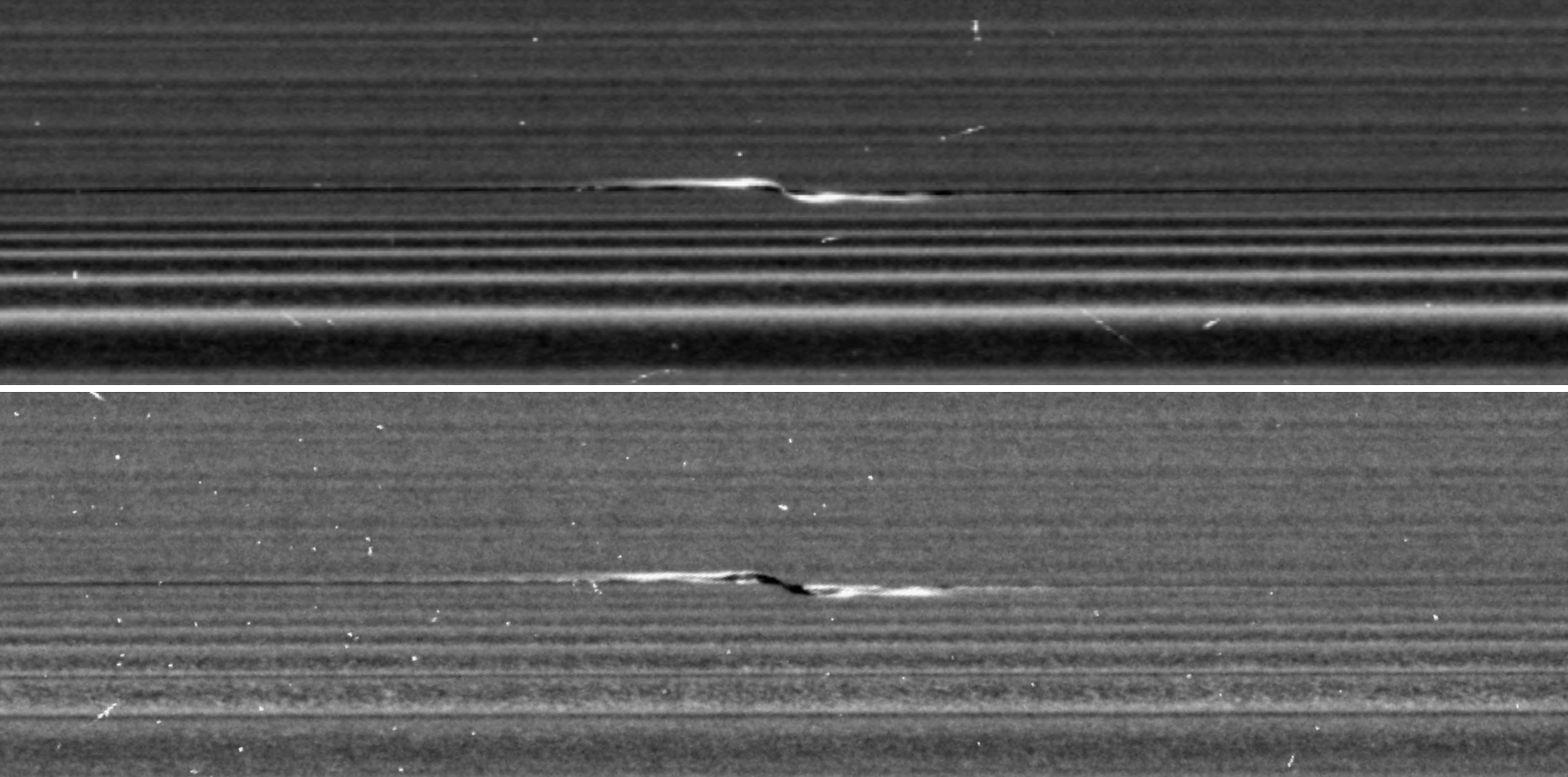

Propeller feature in Saturn’s A ring. (Image NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

Just one day before falling into the atmosphere, Cassini photographed for the last time the rings in which it was able to detail six propeller-shaped structures whose orbits were followed for several years and which bear the names of illustrious aviators: Bleriot, Earhart, Santos-Dumont, Sirkosky, Post and Quimby. In addition to these six propellers, Cassini was able to highlight real swarms of mini-propellers that amazed the researchers. “Cassini made it possible to understand how the gravitational forces of its moons shaped the structure of the rings” explains Ravit Helled, “a phenomenon that was not apparent before Cassini”.

Another enigma should perhaps be solved thanks to the Grand Finale, it is the age and the origin of the rings. Theoretical models have shown that without forces capable of confining them the rings would have been scattered in some 100 million years. The question is : are the rings less than 100 million years old or is there a mechanism that keeps them stable? It seems for the moment that it is the moons of Saturn that allow this stability, the analysis of Cassini’s latest data should teach us a little more.

The Cassini electronic “nose” (INMS) also surprised the scientists in charge of the instrument when during its dive it sniffed the gases that are between the rings and the planet. They discovered that ring molecules “rain” in the atmosphere of Saturn. Even if they were expecting it, they were surprised by the composition of this rain which contains in particular methane which is quite rare in the rings.

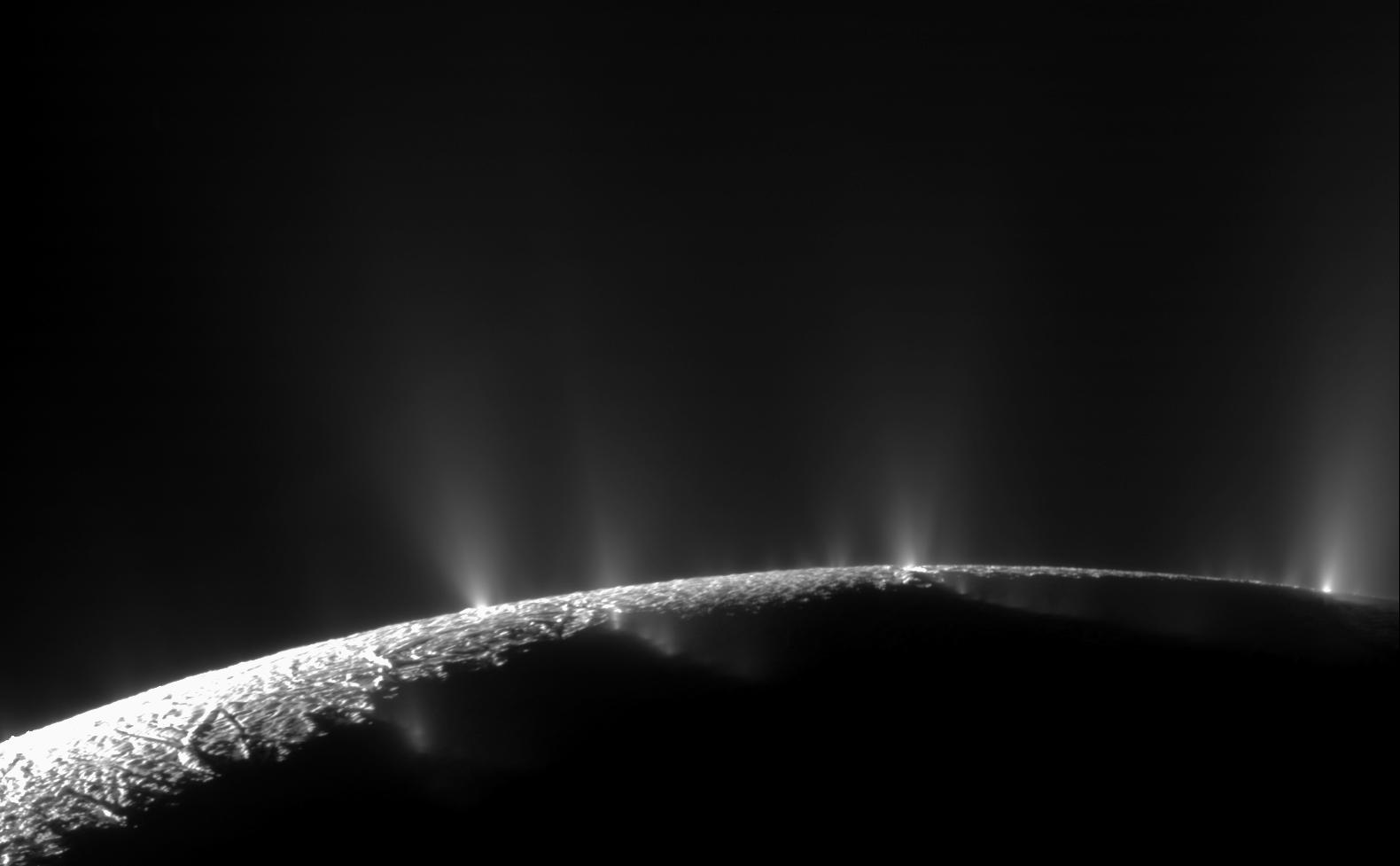

Plumes on Enceladus. (Bild NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute)

The Grand Finale should also give an answer on the duration of the day on Saturn, or in other words on the period of rotation of the planet thanks to the measurement of its magnetic field. Astronomers seek to know if the magnetic field has a detectable inclination. According to Michele Dougherty, head of the magnetometer at Imperial College London, the sensitivity of the instrument was multiplied by 4 during the Grand Finale which allowed a precision of 0.016 degrees on the angle of magnetic field inclination. A very small inclination would test current knowledge of how planetary magnetic fields are generated, suggesting a more sophisticated dynamics within Saturn.

One of Cassini’s most sensational discoveries is undoubtedly the geysers of water coming out of the surface of Enceladus. “This suggests that there is an ocean under the ice crust, with hydrothermal activity” says Ravit Helled, “there are different proposals at ESA and NASA with the goal of studying Saturn even further, “says the astrophysicst, adding that with NASA’s JUNO mission and ESA’s JUICE project, it’s Jupiter and its satellites that have priority. “I’m sure we’ll one day return to Saturn to study its rings and moons,” concludes Ravit Helled.

Categories: External Newsletter