NASA’s Chief Scientist visits Bern

Are we alone in the universe? «This is one of the questions that drives us forward», says Ellen Stofan, NASA’s chief scientist, who is convinced that we will find an answer in the next 20 years: «That is terribly exciting.»

A special guest was welcomed by members of NCCR PlanetS on Feb. 25th 2015: NASA’s chief scientist Ellen Stofan spent the day at the University of Bern visiting different labs, discussing current projects and describing the US-American space agency’s vision and interests in planetary science.

One of NASA’s main goals is a manned mission to Mars. Do you really think that one day humans will get to our neighbouring planet?

Ellen Stofan: I do think we will get there, and I don’t think I am just being optimistic. We are on a path that really looks out for what are the things we need to focus on in the next twenty years to actually make this happen. But it is not just something NASA is going to do. We are going to do it with international partners in cooperation. It is a very different model than how we sent humans to the moon.

Your father worked as a rocket engineer for NASA. So you have been familiar with the agency since you were a child. How has it changed?

I went on my first launch when I was four. I prefer looking at the ways that NASA hasn’t changed because to me it is about innovation, about explorations, about people working in teams creatively. What has changed since those days is that those teams are now international teams. I worked on the Cassini mission. Our science team was an incredibly international team. The world in that sense has become much smaller than it was in the 1960s.

But the budget got also much smaller.

That certainly has changed from days back of Apollo. At that point NASA had a much bigger share of the federal budget. But on the other hand our budget this past year was over 17,5 billion dollars. That is an awful lot of money. So we were able to use that money to do things like having 19 spacecraft studying the earth and how it is changing. We are studying stars, planets around other stars or our solar system. We are studying our sun as well as supporting the astronauts up on the International Space Station. So we were able to take that money and leverage it for an extremely rich program.

In Europe and especially in Switzerland we sometimes get the impression that the Americans don’t take us seriously.

That is surprising to me to hear that. We take our partnerships with space agencies around the world very seriously. We do everything in partnership with other countries. You have to go all around the world to get the best minds to solve the really tough problems. We also have a long history of cooperation with Switzerland going all the way back to Apollo. And I can name mission after mission that we worked on with Switzerland. That has been important and critical to broadening scientific knowledge of our sun, our solar system and the universe beyond. It is a critical partnership and we wouldn’t succeed unless we all work together.

If you had one wish and got the answer to one scientific question, what would you like to know?

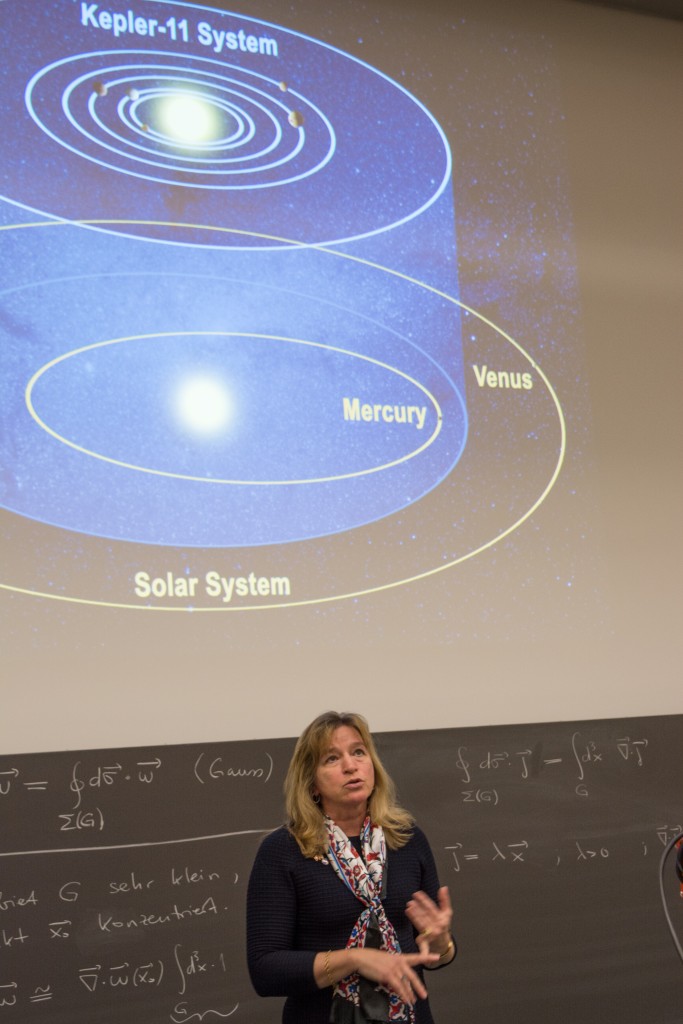

My favourite question by far is: Are we alone? It is one of the questions that drive us forward. It’s why we explore Mars. Mars had water on its surface for long periods of time. Did life evolve on Mars? Jupiter’s moon Europa has a subsurface ocean that could contain life. Looking for planets around other stars is what motivates us to find a habitable planet and then maybe eventually detect signs of life. I actually believe that in the next 20 years it is a question we will be able to answer. We will find life after Earth. I think we are going to find some exciting signs in the atmospheres of extrasolar planets that we are studying. We are on the verge of actually getting some answers to this fundamental question humans have wondered about ever since they looked up at the stars. That is terribly exciting.

But we won’t be able to visit life elsewhere.

Certainly not on extrasolar planets. At this point like with CHEOPS, the spacecraft that Switzerland will launch, our ability is to detect planets, to say how big they are, how far from their parents’ stars they are. With instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope we are going to be able to start studying their atmospheres. But in terms of actually visiting? We still use the same propulsion technologies that we basically used back in the 1960s with not a lot of improvement. When I go out to schools I always challenge the kids. I say this is why we need you to go into science, technology, engineering and math careers because we need you to go and invent that new propulsion system that will get us to another star.

How did you manage to balance raising your own children with your career as a top scientist?

I have three children. They are 26, 22 and 19. They are all wonderful, but none of them are scientists. For a big part of my career I actually worked part time. And for part of that time I worked at home. But I was able to keep doing research. I would just publish fewer papers than my colleagues. But I always tried to stay involved and balanced as best as I could, while raising my children. Now they are grown, and I have more time. So I was able to come back and work full-time at NASA. I think that is the important part when I talk to younger women who are a bit intimidated about going into a career that is really demanding. It is all about making balanced choices. But to some extend science is a great career to go into because you can go back to working less hours and then go forward to working more when your children get older. So it is a great career for flexibility, whether for women or men.