30 years ago

Exactly 30 years ago, on October 6, 1995, the University of Geneva Observatory changed our view of the world with the announcement by two scientists, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, of the discovery of the first planet orbiting a star other than the Sun. However, it was in the 1970s that Geneva scientists began developing instruments to measure the speed of stars and potentially deduce the presence of exoplanets. More than 40 years of instrumental development and research into precision spectroscopy and exoplanets will be recognized on October 10 with the UNIGE Innovation Medal at the Dies Academicus. Geneva, along with the rest of Switzerland, has everything it takes to maintain this expertise and remain at the forefront of research into exoplanets and life in the Universe.

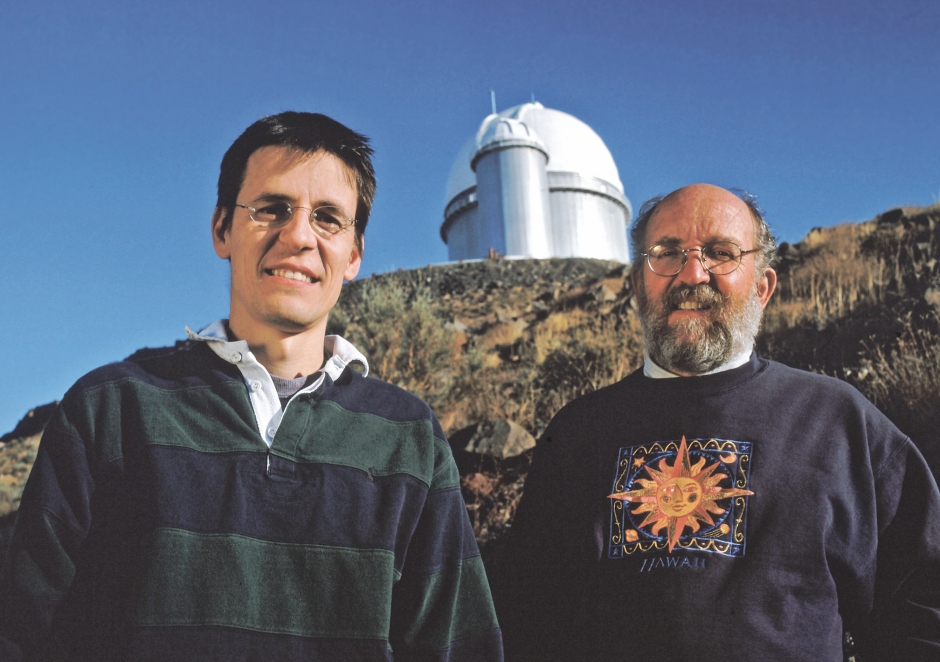

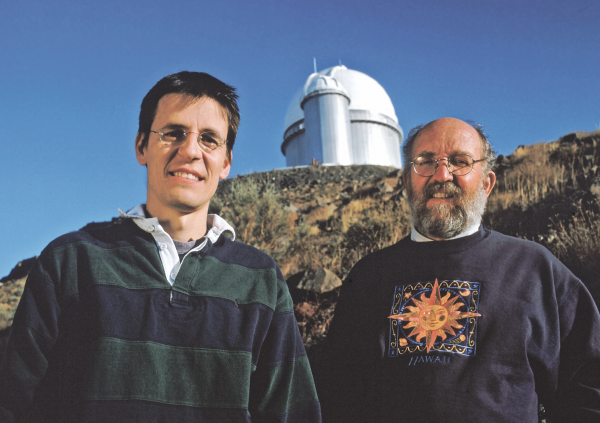

World-renowned Swiss astronomers Didier Queloz and Michel Mayor of the Geneva Observatory are seen here in front of ESO’s 3.6-metre telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile. The telescope hosts HARPS, the world’s leading exoplanet hunter.

Crédit: L. Weinstein/Ciel et Espace Photos

Since the middle of the last century, astronomers have believed that planetary systems originate during the formation of stars themselves. There are therefore hundreds of billions of planetary systems in our Galaxy alone, provided they can be detected.

As early as the 1970s, a new method developed at the Geneva Observatory allowed for precise measurement of the velocity of stars. However, it turns out that a planet, even a small one, creates small oscillations in the velocity of its host star. In the late 1980s, Michel Mayor and an optical engineer, André Baranne, began designing a new instrument to be installed on the 2-meter telescope at the Haute-Provence Observatory in southern France. The instrument was a success and allowed for measurements of unexpected quality with a precision that opened the possibility of detecting planets as massive as Jupiter.

First Observation Program

In October 1993, Michel Mayor submitted a request for telescope time to attempt to detect exoplanets: one week of telescope time every two months, 42 nights a year! Despite fierce competition for observation time, the request was accepted. Joined by his doctoral student at the time, Didier Queloz, the two astronomers decided to focus on 142 stars comparable to our Sun… the quest for exoplanets had begun for the Swiss.

At the end of 1994, Didier Queloz, who was leading the observations for this “exoplanets” program at the time, sent a fax to Michel Mayor, who was visiting the Hawaii Institute for Astronomy: “A star exhibits variations that appear periodic, with a period of only 4.2 days. What do you think?”

Caution before discovery

The observed variation for the 4.2-day signal would correspond to a planet with a mass half that of our Jupiter. However, the formation of giant planets occurs at great distances from the star, where orbital periods are on the order of several decades, as is the case for gaseous planets in the solar system such as Jupiter or Saturn.

Michel Mayor is therefore cautious. Since 1943, the field of extrasolar planets has already seen too many discovery announcements that have proven to be completely false. He therefore proposes the only fair and reasonable thing for a scientist to do: make new observations to eliminate all possible alternative interpretations.

It was not until July 1995 that the star was again visible in the sky over southern France. The new measurements supported the planetary hypothesis. In the heat of the Provençal summer, the two astronomers and their family celebrated at the “Clairette de Die.” The results were published in the journal Nature and the announcement was made at a conference in Florence on October 6, 1995, thirty years ago. Incidentally, the discovery would earn the two scientists the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2019.

International recognition and continuity

After observing the Northern Hemisphere, Geneva astronomers moved into the Southern Hemisphere in 1998 with the 1.2-meter EULER telescope and an ambitious exoplanet detection program. This observation program continues today. Its continuity and consistency over 27 years make it an indisputable asset for exoplanet research, as it allows for the discovery of planets with very long periods. Sometimes, science requires patience.

Geneva’s expertise in high-precision spectroscopy for exoplanet research is internationally recognized. The European Southern Observatory (ESO) has agreed to entrust Michel Mayor with the installation of a new spectrograph, HARPS, to equip the 3.6-meter diameter telescope at its La Silla site in Chile. This new planet hunter got installed in 2003… just a few steps from the EULER telescope.

The excitement surrounding the 1995 discovery helped firmly establish exoplanet research at UNIGE and in Switzerland. The Swiss National Science Foundation awarded UNIGE and the University of Bern (UNIBE) a National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) dedicated to planetary research in 2014, PlanetS, which notably helped galvanize Swiss resources for the CHEOPS space telescope launched in 2019.

In 2018, under the direction of Professor Francesco Pepe of UNIGE, the world’s most precise spectrograph, ESPRESSO, was installed on Mount Paranal in the Atacama Desert. This instrument, which achieves a sensitivity of 10 cm/sec, makes it possible to detect planets with masses similar to that of Earth. In 2023, under the direction of Professor François Bouchy of UNIGE, the NIRPS spectrograph got installed alongside HARPS to track exoplanets in the infrared.

Always more and a reward

To remain competitive and continue pushing the boundaries of human knowledge, the Observatory of Geneva is already working on its next instruments. One such instrument is RISTRETTO, headed by Professor Christophe Lovis, which will allow us to observe the light from the nearest exoplanet around the star Proxima Centauri. This instrument will also serve as a prototype for a project already underway for the giant 39-meter telescope that ESO is currently building in the Atacama Desert on Cerro Armazones.

To recognize past innovations and the expertise developed over the past 40 years in precision spectroscopy, and to support future projects, UNIGE has decided to award the Observatory the Innovation Medal during Alma Mater Day, the Dies Academicus ceremony on October 10th.

Switzerland can maintain its lead

The 30th anniversary celebration allows us to measure how far we’ve come since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b. But the race for planets continues with a clear long-term goal: the search for life elsewhere in the universe. This is indeed the goal of several research centers, including institutions from the NCCR PlanetS such as the one at ETHZ (National University of Zurich) with Didier Queloz and the one at UNIGE (University of Geneva) with Michel Mayor, headed by Professor Emeline Bolmont. This Center for Life in the Universe (CVU) adopts a transdisciplinary approach, bringing together not only astronomers but also scientists from other departments of the UNIGE Faculty of Science, such as geologists, chemists, and biologists.

Switzerland, and Geneva in particular, thus holds the keys to successfully shake up humanity’s place in the universe once again.

Categories: News