Stars with planets show no special fingerprint

With the participation of the NCCR PlanetS, an international team of scientists has determined the chemical composition of 84 stars with great precision. Contrary to popular scientific theory, their results show that there seem to be no clear chemical differences between stars with and without planets.

An artistic representation of two stars, Kepler-68 and Kepler-100, and their chemical “fingerprints”. Picture: Tobias Stierli

For 25 years it has been known planets orbit not only around the Sun, but also around other stars. Since then, scientists have found more than 4000 planets orbiting a multitude of stars. Around massive stars and light stars, around relatively hot stars and around rather cool ones. It seemed as if every kind of star could have planets.

But through some studies the theory arose that stars with planets have a certain chemical composition. The origin of this theory was the chemical peculiarity of the Sun – its “chemical fingerprint”, so to speak, compared with similar stars. Other studies that found similar chemical fingerprints on other stars with planets have supported the theory. This pattern, if it really applied to all stars with planets, would mean that when searching for planets, you could specifically look for stars with the matching fingerprint. This would be a great help to astronomers. But this pattern does not seem to be so clear-cut, as contradictory study results have also been published.

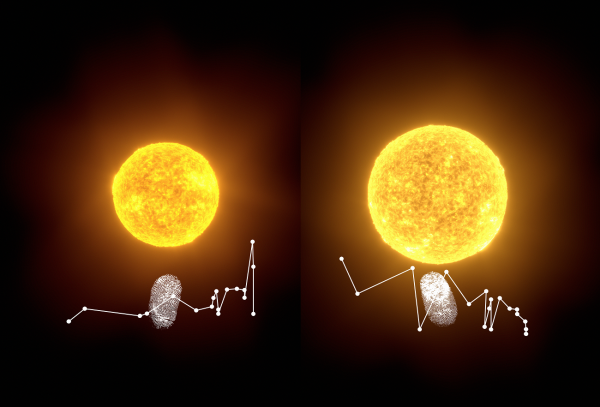

Gravity, temperature and metallicity (colour) of the 16 planetary stars (circles) and the 68 reference stars (crosses). Source: Liu et al (2020).

In order to clarify whether this pattern actually exists or not, a team of scientists, including ETH researcher and PlanetS member Haiyang Wang, studied the chemical composition of 16 stars with planets – including our sun. They then compared these “fingerprints” with those of 68 stars without planets, but which otherwise had similar properties. So similar temperature, gravity and metallicity – a measure of the abundance of elements other than hydrogen and helium.

Precise measurements

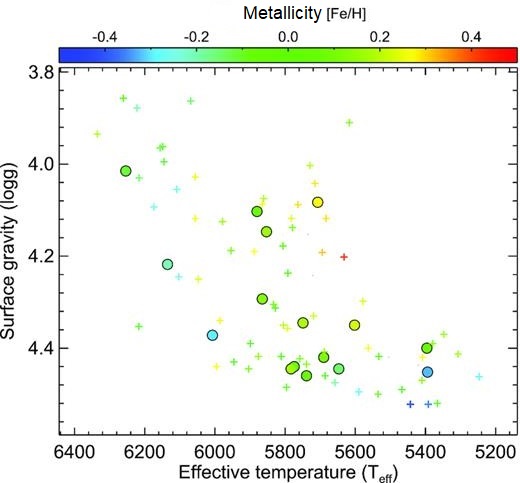

For their investigations, the team used the 10-meter Keck telescope – one of the most powerful telescopes in the world, located in Hawaii at an altitude of over 4000 meters above sea level. “With the help of its HIgh Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES), we split the light from the stars into its respective wavelength components – similar to a prism that splits white light into the colors of the rainbow,” explains Haiyang Wang. Using the star Kepler-68 as an example (following figure), it is possible to see which parts of the light are absorbed by the elements of the star by troughs in the signal. This is because the positions of the troughs are characteristic for each element. The strength of a particular trough in turn indicates how much of the respective element is present on the star.

The measured light of the star Kepler-68 with signal troughs showing the absorption of the respective marked elements. Picture: D. Yong; Data processing: F. Liu, H.S. Wang and D. Yong.

“This allowed us to measure the presence of 19 different elements such as carbon, oxygen, sodium, magnesium, calcium, iron and nickel in each of the stars,” says Wang. Using analysis techniques they had developed themselves, they were able to create very accurate “fingerprints” of the stars.

.

Dr. Haiyang Wang is a postdoctoral fellow in the Exoplanets and Habitability Group at ETH Zurich.

The results partly confirmed what earlier studies had found out: “The Sun is actually chemically different from its comparison stars,” as the lead author of the study, Fan Liu of Swinburne University of Technology, explains. In particular, it lacks those elements that are the main building blocks of terrestrial planets such as our Earth, Mars and Venus. The lack of these “planetary building blocks” on the Sun had led to the theory that this might be related to the formation of the planets in our solar system. The question that Wang and his colleagues tried to answer: Is it the same for all stars with planets?

Different fingerprints

Their answer: No. “We did not find this pattern of the Sun in all stars with planets,” says Wang. Rather, their results show that these stars have a great diversity in chemical composition, relative to their comparison stars, that were not known to have planets.

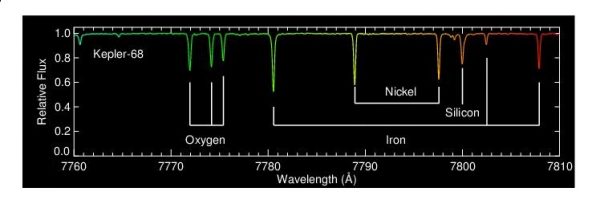

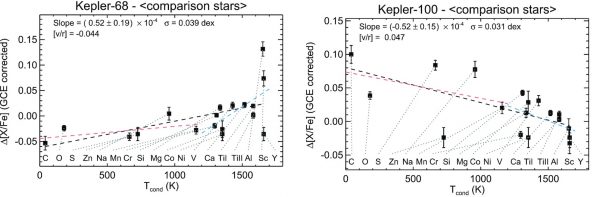

This becomes clear, for example, when comparing the stars Kepler-68 and Kepler-100 (figure below). While Kepler-68 has a similar fingerprint to that of the Sun, this is not true for Kepler-100 – even though both stars have planets. This shows that planets can orbit around chemically different stars.

Element abundance of the stars Kepler-68 and Kepler-100, which have both planets, relative to their comparison stars. The “fingerprints” are quite different. Source: Liu et al (2020)

Questions remain

Even though the team’s results do not show clear chemical differences between stars with and without planets, they do not rule out that this pattern may yet exist. One reason for this is that the results are based on the assumption that the reference stars have no planets. But Wang points out: “Although no planets have been discovered around the comparison stars so far, at least some of them might actually have planets”. Rather than indicating the presence of planets, the pattern could then be an indicator of how evenly the elements were distributed in the early star system. Or how efficiently the planets accumulated these elements during their formation.

In any case, the detailed “fingerprints” of the stars give the scientists idea of the kind of planetary compositions that can be expected in the respective system. “Know the star, know the planets”, as study co-author David Yong from the Australian National University puts it. Something that Wang and other members of PlanetS in the Exoplanets and Habitability group at ETH Zurich plan to look further into, as Wang says: “We are now using the results of the stars with planets to study the inner composition and structure of the planets”. In the long term, the stars’ “fingerprints” could thus accelerate the search for potentially habitable Earth-like planets.

Reference:

Detailed chemical compositions of planet-hosting stars – I. Exploration of possible planet signatures, F Liu, D Yong, M Asplund, H S Wang, L Spina, L Acuña, J Meléndez, I Ramírez, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa1420