“Now CHEOPS is ready for transport to Kourou”

The space telescope CHEOPS is foreseen to launch in the last quarter of 2019. “In July, we carried out the final tests on the instrument at Airbus in Madrid,” says project manager Christopher Broeg: “Now CHEOPS is ready for transport to Kourou.”

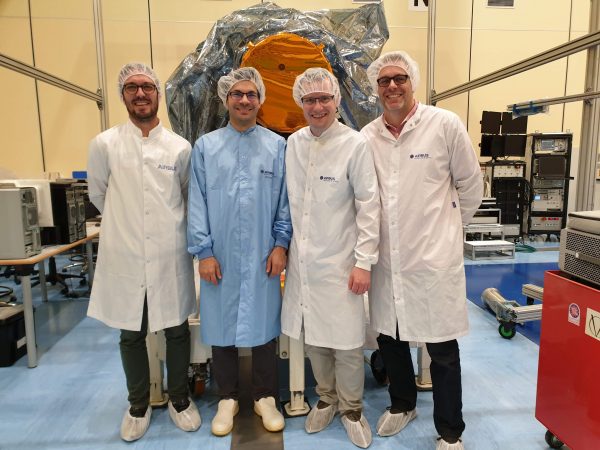

At Airbus in Madrid from left to right: Thomas Beck (UBE, System Engineer), Daniel Matter (Ruag Space/ADS Spain, AIV support), Roland Ottensamer (UVIE, CHEOPS instrument S/W), Christopher Broeg (UBE, Project Manager). (Photo ADS Spain)

PlanetS: The work on the CHEOPS space telescope was actually completed months ago and the satellite was mothballed at Airbus in Madrid. Recently, however, the CHEOPS team travelled to Madrid again. What for?

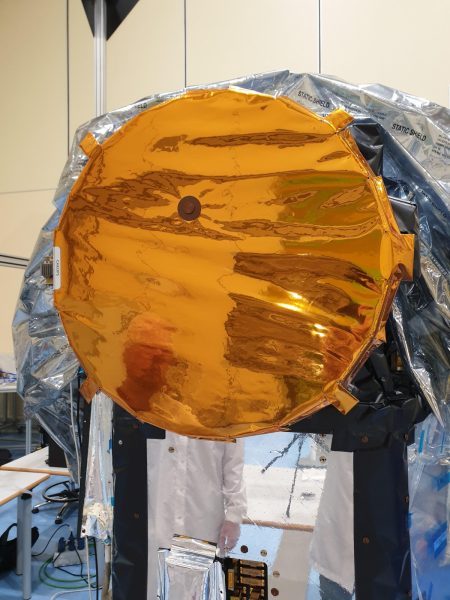

Dr. Christopher Broeg: We did a few tests again, as is usual after mothballing a satellite. Among other things, we did a final test where light hit the detector. There was a small hole with a glass pane on the front of the lid. We wanted to make sure that no additional dust particles and no more “bad pixels” were added, i.e. pixels that were too bright or too dark. We looked at the current image and compared it with the last one taken nine months ago: It looks exactly the same. So, everything is fine.

Will the hole in the lid stay open?

No. When we fly, it has to be closed, because once in orbit, we want to take dark images first. That’s why we’ve already closed the hole, because in Kourou it’s always difficult to do anything.

Are there any other tasks to do?

When we left Madrid, the Airbus people still had to mount some things on the spaceship, and check whether the antennas are properly connected so that the connection between transmitter and receiver works properly.

On the instrument side there is now nothing more to do, it is ready for transport to Kourou. The satellite will be packed into a container and flown to Kourou by plane. But there is one last task left on the instrument. A small opening behind the solar panels that is needed for the purging has to be closed. In order to prevent dust from settling in the instrument, a certain amount of highly pure nitrogen is floated through. This must also be done in Kourou, where the satellite is lifted by crane without any protective plastic sheet. Only when everything is ready, you can remove the tube for the nitrogen supply and screw on the lid.

Will the Bernese team be present during this final action?

This is currently not planned. We have shown the Airbus people what they have to do. From now on everything is in the hands of Airbus until 5 days after take-off, when we will start the commissioning of the instrument, which will take 2 months.

Will you immediately realize if everything is all right?

Whether something goes fundamentally wrong is already known the first time you switch the instrument on. At the beginning we take dark images for 2 to 3 weeks before we open the lid. You can see immediately whether something has broken in the electronics. Because even if there is no light and the dark current is very low, you get electrons that you can count with the electronics.

The main risk is if the lid opens. Although this mechanism has been tested many times and has already been used in the COROT space telescope, we will still be nervous. Then, it gets really exciting when you see the first star. You probably wouldn’t notice a broken mirror before and only then will you know whether our focus setting is correct. Ideally, the star would appear as a blurred object, because the instrument is slightly out of focus, because we only want to observe bright stars and the exposure time would otherwise be too short. In the laboratory we were able to simulate space conditions like zero gravity by hanging the telescope vertically and low temperature, but only one at a time.

What is the CHEOPS team doing until the satellite will be launched?

The ground segment still has to be brought into shape. There are a few things in the SOC, the CHEOPS Science Operations Center in Geneva, that are not yet working as desired. The entire pipeline, from observation planning to data reduction, is being tested.

In Bern, we are dealing with the commissioning, which takes place in 2 phases. As long as the lid is still closed, the Flight Operation Procedures (FOPs) are entered manually. Here we have a model that contains all the electronics. This allows us to run all procedures once again, because you can make many mistakes. For example, the frame rate can be too high so that the computer still compresses the data while the next image already arrives.

In the second part of the commissioning, when the lid is open, everything works automatically, just as during the normal mission phase. These procedures have all been tested, but only after the announcement of the launch date we can set the targets and plan and simulate the observation of the selected stars to check if everything works the way we want it to.

The CHEOPS spacecraft has completed its last light excitation test prior to shipment to the launch site. Afterwards, the small window in the telescope cover was sealed with a plastic cover. (Photo ADS Spain)